Posted by Clark Bates

March 22, 2019

Everyone has one. That mountain they're ready to die on. There’s always at least one thing that you will not abandon, no matter how hard you’re pushed. I’m willing to bet that, even if they’ve never thought of one, every person on the planet has a such a position. This is a good thing. I believe firmly that everyone should have convictions and that these convictions should be something that they will fight for. You might say that’s a mountain I would die on.

That’s not to say that we all shouldn’t be willing to be reflective and analyze our convictions over the years, to be certain that we aren’t holding to something that may not be true. After all, circumstances change, new evidence can be revealed, and as Socrates famously said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.”

The question everyone should ask themselves routinely regarding their particular “mountain(s)” is, “Do I need to die here?” Basically, reflect on the issue at hand and determine if it really is absolutely necessary to your worldview that it be true, or that your position never change. I bring this up because the tendency among Christians, and probably everyone else as well, is to make minor details of Christian belief the most important. Having grown up in an IFB (Independent Fundamentalist Baptist) community, I was well-versed in the hundreds of minor details that were “essential” for someone to believe if they were a “real” Christian.

Examples? This may be where I lose readers but there are many. Does it matter which translation of the Bible you use? What about wearing a hat in church? Can a Christian smoke? Drink? Dance? In the world of apologetics, we have many as well. Does it matter how old the universe is? Can you be a Christian and believe in evolution? What if the Gospels were written later than 70 AD? Does it matter if the meaning of a beloved Bible verse happens to be different than you’ve always thought? What if the Canon of the Bible wasn’t ever actually decided formally?

Ask yourself, are these non-negotiables for you, or is there room for differences of opinion? For many years, several of these positions were non-negotiables for me. I would never have agreed that you could believe in an old earth, let alone evolution, and be a Christian. I always believed that the New Testament existed as the 27 books we use today and that there was never any dispute in the matter. And don’t even get me started on dancing (blame the IFB, but hey I was a kid, I didn’t know any better). These days, whether by wisdom or folly, I don’t consider any of the items listed as non-negotiables of my faith. Why? Because Scripture does not affirm them to be, and my knowledge of both the positions themselves and those who hold to them has broadened. Mind you, I do still have mountains I will die on, but these are not among them.

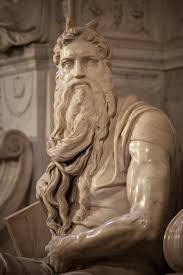

Mosaic Authorship = Biblical Inspiration?

I'm writing this for two reasons, the most important of which is that if you make everything a non-negotiable you will never have a clear grasp of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, because everything will get subsumed into the gospel. If the gospel is everything it may as well be nothing. The second reason is that if you or your children are led to believe that certain things are “mountains to die on” in Christianity, where the Bible itself does not, you are building a house of cards with your faith and it will come crashing down.

I was reminded of the importance of this, earlier in the week when I saw an ad on social media for an upcoming movie seeking to prove that Moses was the author of the Torah (the first five books of the Bible). The tag line for the ad was, “Is the Bible the inspired Word of God? Or is it a book of fables and myths?” Now, if you can’t spot the issue here, what this seems to suggest is that either Moses authored the Torah or the Bible is not inspired and must be reduced to fable and myth. Do you see how tenuous a claim that is? I even asked the question of the company posting the ad, how one would have anything to do with the other. I did receive a reply from another Christian seeking to defend the statement, and he clearly felt it was necessary to believe that Moses wrote the Torah. In our brief discussion, I never stated whether I believed in Mosaic authorship or not, only pointed out that the Bible could be the inspired Word of God even if someone else compiled the stories of Moses and wrote them down. This didn’t go over well, but the conversation remained gracious and for that I’m thankful.

So, allow me to make my point a little more clearly here by using two examples: Mosaic authorship and the authority of the New Testament. I’ll begin by stating that I actually do believe that Moses is the most likely candidate for the author of the Torah, and has traditionally been the author for thousands of years. I also defend both the more conservative dating of the New Testament and the traditional authorship of the Gospels and Epistles. That being said, these are not mountains to die on, and I don’t believe they should be for you either, though I can’t make that decision for you. I only hope you will be willing to hear what I am about to say and take the time to reflect on the matter more.

Mosaic Authorship

Now, allow me to play devil’s advocate for a moment. Modern scholarly consensus is that Moses did NOT write the first five books of the Bible. The most common theory involves several variations on what is known as the Documentary Hypothesis or JEDP.[2] This theory maintains that the Torah was written long after the time of Moses, likely in the 5th or 6th century BC after the exile. What’s more, there is little-to-no Mosaic influence at all, but rather various scribes can be detected within the texts based on their use of the divine names “Jehovah” (YHWH) and “Elohim”, or the focus on priestly functions or revisions of the law. These various scribal works, it is claimed, were then compiled by later editors to create what is now the first five books of the Bible. This theory is clearly, and understandably, offensive to most believers because it flies right in the face of what they’ve always believed, and stands directly opposed to what the first five books of the Bible seem to say. It’s also not unrelated that many who hold to the documentary hypothesis deny most, if not all, the historicity or value of the entire Old Testament corpus.

But here’s the rub, what if they’re right? What if I modified this position just a little bit and pointed out that while Moses is the main character in at least four of the five books of the Law, none of the books are themselves plainly authored? If you look at them again, you might notice that all of them are formally anonymous. Granted, 3 of them begin with the phrase, “then the Lord spoke to Moses…”, but this is the recording of a narrator. The texts are entirely in the third person with the exception of direct discourse. You might say, and some have, that the Torah is formally anonymous in the same way that the Gospels are. In fact, and this is just something extra to chew on, the narrative of the Gospels in relation to Jesus are strikingly similar in form to the narration of Moses in the Torah. No one claims that Jesus wrote the Gospels. Therefore, it is entirely possible that, while the narrations of the Torah contain accurate historical accounts of the manner in which Moses came to be the leader of Israel and the manner in which the nation was given the Law through him, the actual compilation of the books and the narrative that links the stories together was created by another individual(s).

I will pause here to remind you that I subscribe to Mosaic authorship, so the pitchforks and torches can hopefully be put away, but even if the reality is something like I’ve described above, what does it change? In most instances of the NT, Jesus refers to Moses writing something specific contained within the law, which is supported by the account in the OT. Therefore, there is no contradiction in saying that Moses wrote x or even that Moses gave Israel the law, AND there being a third person compiler of these accounts. Does it change the value, quality or inspiration of the Torah or the Bible as a whole, if the author of any of the books is someone other than Moses? Do we not subscribe to the authority of the rest of the OT even though more than 80% of the books are written by unknown authors? Do we not submit to the authority of the epistle to the Hebrews in the NT despite having no knowledge of its author? If you can answer, “nothing changes” then maybe Mosaic authorship isn’t a hill to die on, and it has nothing to do with the inspiration of Scripture. But this also leads me to the second example.

The Authority of the New Testament

Just like above, I will pre-empt my devil’s advocate stance by saying that I subscribe to traditional authorship. There is even an entire page of this website devoted to who wrote the New Testament where I lay out the arguments for that authorship. But here’s the reality, if we set aside our commitments to Christian tradition and what we’ve always been taught, or even what is cleverly argued, there are several books of the NT that are anonymous. While many have taken pains to deciphering how we can be reasonably be sure that the four Gospels were authored by the very men whom they are named after, they are still formally anonymous.[3] Nowhere in the Gospels themselves do the authors plainly identify themselves. In a similar fashion, the epistle of James and Jude do not identify which James or which Jude. Both refer to themselves as “slaves of the Lord (Jesus Christ)” and Jude states that he is the brother of James, but given that both names are counted in the most popular names of the region in the 1st century, any more specificity in identifying them must be based on reasoned conjecture and nothing more. That’s not to say that the reasoning is unsound, far from it, it just means we need to be willing to see the evidence for what it is.[4]

Now, if my position on the Canon of the New Testament or the Inspiration of Scripture relies on apostolic authorship of the books, being faced with this kind of information could destroy my entire faith in the books as a whole. It may even damage my belief in the inspiration of Scripture. However, if I take a step back and really consider the arguments for canonicity, the apostolic qualification for books was NOT about who the author was, but rather if the text carried apostolic authority. So, the test is not authorship but authority. This may not seem like a difference, but it is.

Consider the argument often used that Irenaeus argued that the four Gospels were authored by those to whom they are ascribed. If you look at his actual argument in full, two points emerge:

- He’s arguing not for their authorship per se, but that the teaching contained within the Gospels can be traced back to the teaching of the apostles of Jesus and that they did not require “perfect knowledge” to teach, and

- He’s making this argument in response to the claims of the Gnostics (specifically the Valentinians), that they are the ones who carry the teaching of the apostles.[5]

Now consider the difficulty of claiming apostolic authorship for canonicity with a book like Hebrews. The author is completely unknown! Sure, you can claim that many “think” that Paul was the author, but there’s nothing in the book that states this, and the language of the letter doesn’t match what we see in the Pauline letters. Additionally, while I don’t agree, the arguments against several of the canonical Pauline epistles would suggest that many of the books of the NT are not apostolic. However, when you realize that a book could be written by non-apostles, and several were, without it bothering the church for hundreds of formative years because a book was deemed canonical if it carried the authority of an apostle, all of these arguments against the canon disappear.[6]

Conclusion

There is but one God and He is the Creator of all things.

He has one, only-begotten Son, Jesus Christ, by whom alone salvation is possible.

This man Jesus was truly God and truly man, born of a virgin, died by crucifixion,

was resurrected on the third day and ascended into Heaven.

The Holy Spirit of God has been given to His people through which they will receive power to tell others of the salvation made available to the world.

These are, without a doubt, non-negotiable for the Christian. All other points are ancillary to these, and while they will each have their own level of importance, there will always be room for discussion over them, and there always should be.

So, there is no misunderstanding me, please know my heart on this issue. When I give lectures at a church and I bring up matters such as this, I am quick to point out that one day, the people will hear about these issues. They will either hear it from someone like me or from someone like Bart Ehrman, and I’d much rather they hear it from me. I want the church to be known for its level-headedness and careful thinking. I want Christians to take captive naivete surrounding their faith and be prepared for the opposition they will face in the world. I want them to know the challenges so that their faith takes hold of the fertile soil and digs deep roots, because the birds of the air and the thorns of the deep will come to try to snatch it away and choke the life from them, but a seed sown deep is not easily removed. I will close with a quote from a friend of mine now at Tyndale House in Cambridge concerning the approach to the Bart Ehrman’s of the world:

“The problem isn't 'Ehrman (full stop)', it's 'Ehrman+antagonistic professor+ministers letting Christians hear about this stuff from Ehrman and antagonistic professors first'. Treating it as if Ehrman is the sole problem is a *really* bad idea because it leads to statements like ‘This is why I am wanting an actual list, to be able to demonstrate how deceptive Ehrman is’ and ignores our own failures to let our church members know what's out there before they hear it from someone who wants to use it in a way that would destroy their faith.

Yes, Ehrman sensationalizes his point to draw conclusions that should not necessarily be drawn from the data he gives. But Christians do it too in our desire to respond to/disprove him. It's never a good idea to misrepresent the truth. Far better to be honest about what God has given us. To use a phrase that a couple of friends of mine use, there is a ditch on both sides of the road—don't fall into one of them because you're trying to avoid the other one.”

- Author's note: In no way am I demanding that those who read this article agree with me in my positions, nor by citing other positions (i.e. theistic evolution) am I suggesting that I agree with them. My only desire is that every believer be willing to reflect on the positions they have historically considered non-negotiable and simply ask themselves why those positions are mountains they choose to die on.

[2] J – Jehovah; E – Elohist; D – Deuteronomist; P - Priestly

[3] I find the manuscript evidence for consistent titles of the Gospels, early recognition of the church fathers with these titles and the clear means by which the entire church from its inception were able to distinguish between them (after all you had to know which Gospel you wanted copied for your use) to be substantial in supporting the traditional authorship, or at least, the fact that the Gospels have always been transmitted under the same names as we have today.

[4] This is to say nothing of the challenges to various Pauline Epistles that, especially to those untrained in the original languages, can be quite convincing.

[5] Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 3.1.1 – 3.3.1-4.

[6] By “apostolic authority” I mean that a book could be written by someone other than an apostle (i.e. Jude, James, Mark, Luke, Hebrews) yet contain teaching which clearly corresponded to the teaching of the apostles to the church. If the message of the book met this standard it became canonical. This also helps understand why books like the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Peter, and others were not accepted, even though they were initially used by the church.

No comments:

Post a Comment